Not Long Now

Grandson of Famed Inventor Inherits Mechanical Orphanage

1

Although I never had the pleasure of meeting him, I’m told my Grandfather was a man ahead of his time. I’ve attended no small number of parties at which people I’d never seen until then assured me they knew him, lamented that he died too soon and regaled me with stories of his wondrous inventions. Wasted on me, I fear. I was too young to retain much of it.

Lucky for me that he kept such detailed notes! Reams upon reams of them, filled with the most eye wateringly detailed schematics. Of great, ponderous gears. Of wee little cogs. Of pistons, electrical circuits, boilers, and all manner of fascinating mechanisms.

It resonated with me, even then. Something about the intricacy of it all. The symmetrical, rigid elegance of a complicated machine which I could effortlessly envision in motion. How I would study those pages, luxuriating in all of the clever little details!

All too often it was my bedtime story. I would read it to myself on the nights my father, Victor, worked late. But how I lost myself in it! Page after page of astonishingly precise diagrams. Each one a snapshot of some thought my Grandfather once had. Fragments of his mind, made immortal as ink on paper.

I’ve heard it said that a book is the closest thing to a real ghost: It permits you to step into the psyche of someone who may be long dead. To think their thoughts after the fact, resurrecting some part of that person in your mind for the duration of the book.

Usually whether or not they intended, it reveals something of who they were. An imprint of their soul, if there is such a thing. But then, anyone can leave behind writing. That wasn’t enough for gramps. He did not simply leave behind a book, nor even many. When a man like him dies, what’s left is a grand puzzle.

Sometimes unintentional, as the thoughts of someone like him are indecipherable without considerable education and at least rough knowledge of his or her idiosyncrasies. Not in his case, though. He was very deliberately cryptic. On every page, some of the notes are in plain English, while the rest are in some language I’ve never seen anything comparable to.

Why bother, when the schematics are laid bare? What’s left to hide at that point? If there are any answers to be found, they’re in his journal. Here and there, written around the schematics, are accounts of every day life. Not the sort of things anybody else would have recorded, significant moments in life such as marriage, births, deaths and so on. All of it related to machinery.

“My first sighting of a horseless bus in London was an epiphenal moment. I spent many an idle evening prior to that reading about Francois Isaac De Rivas’ groundbreaking work on motor carriages, but to see one in motion made it real for me.

At last! A compact, practical means of turning stored energy into motion! I know a milestone when I see it. I at once abandoned my own experiments with steam engines, glad to be rid of the mess. Instead, for a time I tinkered with the new thing, internal combustion. Not long now, I thought.”

The page bore technical drawings of what I recognized for early automobile engines fueled by hydrogen, and more recent models which run on petroleum. Yet as the entries went on, he seemed to lose interest in the technology just as soon as he’d been turned on to it.

“Internal combustion won’t do. Noisy, smelly, too much vibration. Then there’s the problem of obtaining fuel. Simply won’t do for what I hope to build.

I’ve overlooked the electric motor for too long, unconvinced of the utility of electricity. But with the advent of alternating current, it now seems possible to transmit energy in a clean, silent, safe manner throughout the superstructure of the machine with minimal losses.

What a wonder it is! A quiet, invisible butler. Or a genie? Able to perform any sort of labor you ask of it, requiring only the correct machine for converting electricity into heat, light, motion, or anything else. This will do. Yes, it will do nicely. Not long now.”

I began to notice patterns. Not just in the cadence of his writing, but that he frequently concluded his entries with “not long now”. Not long until what? The tone changed as the entries progressed, too. He sounded more and more excited. As if he could see something immense and fantastical rushing towards us all. Something which, to the rest of us, is invisible.

“I’ve just returned from a demonstration of the most remarkable invention. Something resembling a cylindrical lightbulb but which performs an altogether more useful function. It’s a sort of switch, triggered by current, which redirects it into one of two channels. The inventor, John Ambrose Fleming, calls it a triode. The press is calling it a vacuum tube.

I’m tempted, but wonder at how useful it can really be to my project. I’ve already designed mechanical computers which can be machined from the same iron as the superstructure. Utilizing triodes would add silicon to the required materials, which means adding a whole floor to the structure just for producing it.

Before I got my hands on Charles Babbage’s notes, I meant to perform all of the computing via pneumatics. Thank goodness I found a way out of that dead end! It’s been a chore trying to keep the size and complexity down. It only deepens my appreciation for the elegance and efficiency of the solutions nature arrives at, when I compare them to my own clumsy efforts.

Whether triodes prove to be worth the added complexity is uncertain. I will have to build my own for evaluation. At least I’ve put fuels, compressed air and other impractical mediums behind me. It’ll be purely electromechanical going forward, which greatly simplifies my work. Not long now.”

I heard the coach driver call for me from upstairs. I let myself get so immersed, I forgot about the poor fellow waiting patiently for me to return with whatever I meant to bring. Grandpa’s will entitles me to his notes and whatever personal effects I care to take from this dusty old workshop...but there isn’t room for much in the coach.

I carefully stepped over great rusty driveshafts, discombobulated control panels filled with gauges and knobs, trailing frayed wires all over the place. A whole wall was given over to nickel batteries, costly galvanic cells he must’ve used to store energy from the water wheel. I tried to lift one, but couldn’t so much as budge it from the rack. To one side, I spied the corner of some brittle paper slip poking out, so with great care I withdrew it.

An irritated beep of the carriage horn sent me scrambling up the stairs. Soon enough I’d packed everything from the ramshackle cottage I meant to take with me, and we resumed our journey. On the way, as every little bump in the road jostled me about, I struggled to read through a brittle pamphlet I’d found tucked away with the batteries.

“The Manifesto of Futurism”. A curious screed that the foreword identified as Italian in origin, having since been translated into a number of other languages including English. I could at once see why Grandpa might’ve possessed such materials.

It spoke of machines. Of clean lines, efficiency and speed. It glorified the breakneck pace of technological progress and the virtue of violent, unrestrained ambition. For all of its vigor and bravado, there was a conspicuous lack of warmth. Of recognition for the central importance of life, of human relationships.

“Somethin’ wrong? You look off balance.” The driver peered over his shoulder at me just a bit too long for my liking. I admonished him to return his gaze to the road. Perhaps a bit too harshly? He doesn’t know about the accident.

I intimately recognize the sort of person who writes such material. Enamored with whatever the new thing is. Always in a hurry to inhabit the future, disdainful of the present as though it is already the distant past.

Always immediately tired of their most recent achievement. Never satisfied being who they are, when they are, where they are. Always baffled as to why they’re perpetually unhappy. Unable, despite their intellect, to recognize the loop they are stuck in which deprives them of comfort and familiarity.

What a banal way to be. Relentless, a sort of mania which grips the mind, permitting no respite. No weakness is tolerated, no inefficiency. No color, nothing vague or sentimental. Machine men, as I once heard them described. With machine hearts, and machine minds.

To think that I came from such stock! Yet I detest automobiles. The cacophony of honking horns, screeching tires, sputtering engines and shouted vulgarities. The speed, the confusion and fear. All too fast, out of control, lives hanging in the balance.

Like those of my parents. I am not so blind to the workings of my own heart that I fail to recognize the role their deaths played in my lingering disdain for the automobile. I was too young to understand it at the time. All just a stupefying blur of sound and movement.

Peaceful at first. The subtle rumble of the engine. A gentle shake as we passed over each bump. Then excited shouting, followed immediately by screams. The whole car lurched. From the back seat I caught momentary glare from the other car’s headlights between the silhouettes of my mother and father....just before it smashed them into jelly.

I witnessed only a split second of it. How easily a pair of colliding metal hulks can tear someone apart. How effortlessly the wreckage impales their soft bodies. What fragile creatures we are, in the end. I’m told I was found wedged in the space behind and under the back seat. Anywhere else and I’d be with my parents now.

A long, terrible, cold journey awaited me in the aftermath. Step by step through the gauntlet of suffering that follows unbearable loss. Without knowing anything else about a man, by looking in his eyes you can know in an instant if he’s been down that path as well. Doesn’t matter how long ago, the changes are permanent.

Seems surreal that life goes on. That you could be gutted so completely, busted down to nothing so many years ago, yet be sitting here today in perfect health. An absurdity! Nearly tantamount to pretending that it never occurred.

But life kept happening to me regardless. I kept waking up each morning, kept putting food in my mouth, chewing and swallowing it. Damn me. Not strong enough to live, nor strong enough to die. That’s how it happened. Unbelievably, I recovered. More or less.

The hardest thing was accepting the authenticity of it. That I’d not somehow fooled myself but was really, at long last, re-engaging with life. An insult to their memory is how it seemed to me at the time. That I failed to spend the rest of my days in rags, weeping in some forgotten corner, and instead was restored to some semblance of sobriety.

I’ve been happy since then. Not frequently but I cannot deny that, here and there, I have found moments of sincere enjoyment. However terrible it often is, life is also heart wrenchingly beautiful. The ratio between those two is lopsided, but not so severely that I didn’t eventually persuade myself to live.

It turned out to be much less convenient than the alternative. I was handed off between various friends of Grandpa. Hot potato. Only so much charitable sentiment to go around, usually I was never with any one family longer than a year. It made me wonder to myself on occasion how close they really were to the old man.

Once I finally arrived at the caboose of that sequential train of temporary accommodations, there was no place left to put me besides the orphanage that Grandfather devoted his twilight years to building. To everybody’s confusion, particularly newspapers which were concerned at all with the philanthropic endeavors of industrialists.

He was and still is regarded as a brilliant man. But out of everything ever said about him by his admirers and critics alike, nobody ever accused him of being an altruist. Not that he was cruel either, just indifferent to everything except whatever project currently commanded his focus.

Why should such a man, whose soul if he had one consisted of angular metal shapes, all of a sudden become preoccupied with the plight of orphans? As mysterious as the man himself. Of course nobody complained, and in fact many public figures applauded his humanitarian detour.

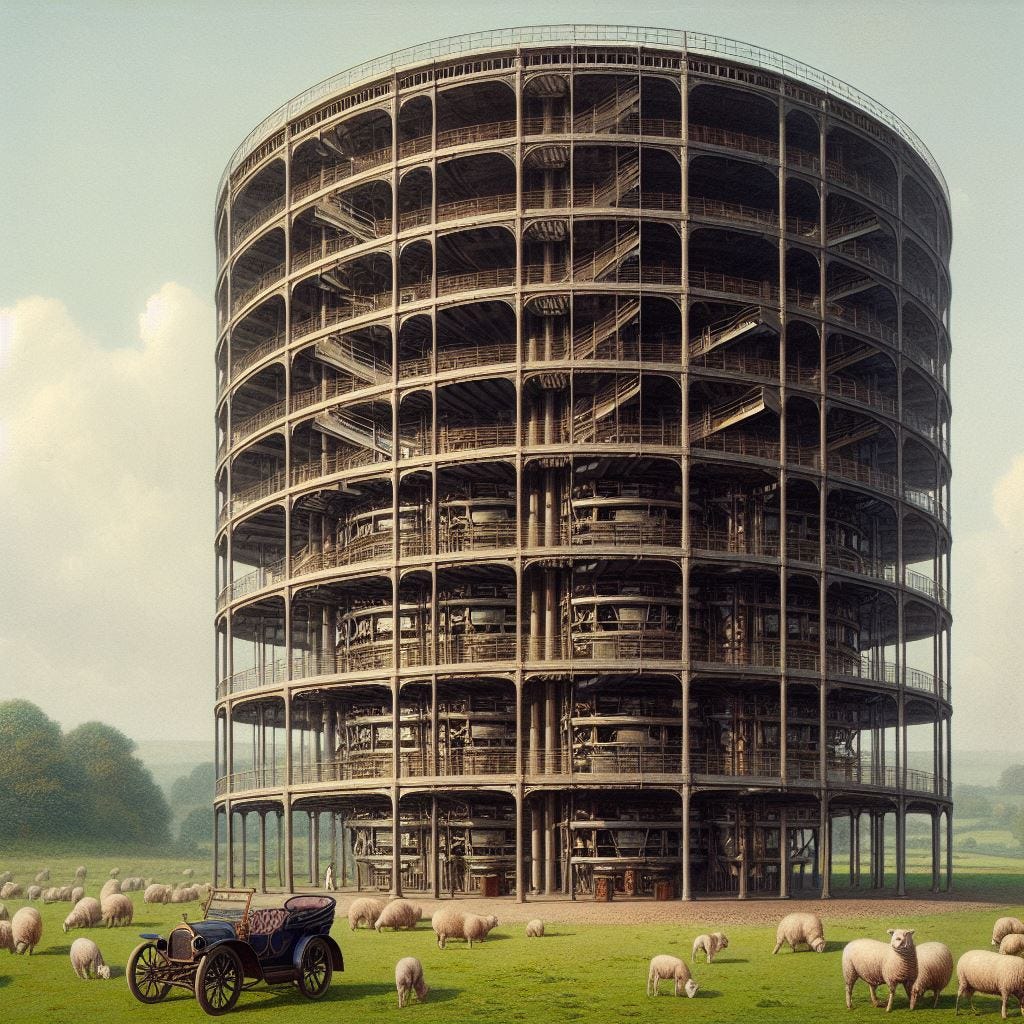

I suppose I should include myself among the grateful masses. If not for his orphanage, I’d be on the street now. Easy enough to see, as the massive structure loomed into view over the horizon, why the city felt it permissible to close down their own such facilities. Grandpa’s orphanage could accept all of the city’s unwanted children several times over.

The motor carriage came to a juddery stop before the immense building’s great double doors. Nowhere else to go now but through them. It was the work of perhaps ten minutes to unpack everything, then the carriage bumbled back the way it came, belching little black clouds of putrid exhaust along the way.

The land around the structure looked to be cultivated into a variety of farms and orchards. Made some sense of where they might get the firewood which must surely be the source of the great, billowing plumes of smoke issuing forth from various tall, thin industrial chimneys poking up through the roof.

“Gracious! Would you like help with your bags?” I didn’t even hear the doors open. The woman approaching me looked no older than twenty, with a pointy nose somewhat reminiscent of a beak and neatly combed brown hair cut nearly as short as my own.

“I’ll be alright” I answered. “I should hardly want to trouble you with any extra work on my behalf when I’ve only just arrived”. She briefly introduced herself as Agnes Stuttgart. Then, rather than lift any of my overloaded bags, she hurried to hold one of the doors open that I might pass through while my hands were otherwise occupied.

“I can’t imagine what it’s all for” she wondered aloud as I heaved it all indoors in serial loads. “Miss Alice provides everything we need.” A curious thing to say, it seemed to me. But before I could ask about it I was hurried along to what I inferred, upon arrival, were my accommodations.

“No doubt meager compared to what you’re used to, but as you’ll see later, it’s a marked improvement over the typical bunk rooms. On account of your relation.” Her tone sounded uncomfortably deferential. Yet another stranger who seemed awed by my lingering, tenuous connection to someone long deceased.

As yet I’ve done nothing more remarkable than to be born into this family. And father, for all his dogged toil, nevertheless also depended greatly upon the social cachet Grandfather amassed during his storied career as an inventor and industrialist.

It is one thing to cast a shadow which your children cannot escape from during your life. It is quite another to cast a shadow which blankets multiple generations. Yet that shadow, and the contents of his countryside workshop, were all he left to us.

So however I might feel about leveraging the power of his name in certain circles, I could do nothing else if I planned to survive. Though his writings often expressed frank references to his own mortality, he nonetheless lived as though his own life was secondary to his goals...if it mattered at all. He’d accordingly set aside no money as inheritance, putting every last dime towards this orphanage.

“Right this way”. She guided me down a long, curved corridor flanked by vertical support beams. All of it iron by the looks of it. In places, the corridor was not fully assembled or blocked off from the rest of the structure. It afforded me occasional views, through those gaps, of the larger superstructure.

I was about to ask where all of this metal came from, but the answer became clear once we rounded the corner. The right side of the corridor now opened up into a round, deep shaft into the Earth. A cold, rusty handrail conspired to prevent onlookers from falling in.

Distant echoes of machinery at work wafted up the shaft, and when I peered as far over the edge as I felt inclined to, I saw an intermittent flash of sparks at the bottom. “Mind your station” Agnes scolded me, without bothering to explain what she meant.

I took it for an imploration to follow more closely, so I did. It was nevertheless difficult not to marvel along the way. Leave it to Grandpa to over complicate an orphanage. What I’d seen so far was closer to a vertical factory, albeit somewhat more fit for living in.

Another gap in the corridor revealed a great pair of lazily turning gears, each at least as large in diameter as I am tall. Just behind them, a row of pistons churned away. I’d assumed the metal was brought in elsewhere. Impressive, but unorthodox, to extract it on site.

Wherever a structural component had been stamped out of sheet metal, there were decorative inset designs. Similar to a bas relief. He must’ve designed it to do that just because he could I suppose. Because if you’re stamping metal shapes anyway, it doesn’t cost much more to include appealing patterns.

We soon arrived before a door in the wall resembling the oblong hatches of a sort often seen in the bulkheads of a ship. “You’ll find everything required for your comfort inside” Agnes advised. “Dinner is at eight, you’ll hear the bell. Don’t dawdle, Miss Alice says we’re to mind the schedule.”

There it is again. But she was gone before I could ask. I made note to bring it up at dinner. If there are certain people I should know better than the rest to fit in here, I’ll make it my business to.

The room didn’t really disappoint, but then I wasn’t expecting much. Very much like a cabin aboard a ship, except so far I’d seen no windows. Would’ve been nice to at least have one in my room, that I might wake to the sun’s rays.

I spent perhaps two or three hours unpacking and otherwise settling into the modest space. With the book splayed open across my desk, I turned my attention to the edges of envelopes sticking out from between later pages.

How did I miss these before? Pressed flat as a dried flower, they looked to be letters Grandpa intended to mail out before death robbed him of the chance. The first was addressed to a Franklin Lutwidge, head of the Ministry of Child Welfare.

“In response to the letter which I received from you on the fifth of May, I certainly am flattered by your kind words and grateful for the city’s generous land grants, which I understand you were instrumental in securing.

But I tell you in truth my dear man, I am only too happy to receive as many needy children as you can authorize transfer of. The poor little poppets will be washed, clothed, fed and put to work in support of the orphanage the moment they arrive.

With respect to the writings of one Thomas Robert Malthus which you saw fit to quote, I am of quite a different mind. Already, his predictions have been repeatedly frustrated by technological developments which have staved off the mass starvation his acolytes seemingly yearn to witness.

They will always be frustrated! Watch and see if it isn’t so. Man does not expand his numbers as blindly as yeast, the paramecium or wild rabbits. He is a creature of foresight and intellect, able to anticipate problems and act ahead of time to mitigate them.

So it is that, when I thought to direct my attention to charitable matters, I reasoned that it would not do simply to hand money out like so many stockings filled by Father Christmas. Spent within the week, then where does it leave you?

Money is like fuel, my dear fellow. You can burn it to stay warm, but it will soon be exhausted. Or you can construct an engine with which to extract yet more fuel in a self-reinforcing cycle. The engine is of course industry! Business! Learning to fish, in Biblical parlance.

I then thought to invent some new industry I might preferentially hire orphans into, making candies or trinkets of some sort, putting most of the profits towards their care. But then, what happens to it when I’ve expired?

What’s really needed to tackle the problem of feeding, clothing and housing the world’s poor is more ambitious than a jobs program. Why is it that they want for basic goods? They haven’t the money. Why do those goods cost money? Some fellow made them, and wants his labor to be compensated.

But what if the various industries necessary for the provision of man’s basic needs could be consolidated into a single building? What if advanced forms of the industrial automation technologies now entering common use were all leveraged therein, such that the whole mess ran itself?

Why, the beggars, orphans and invalids of the world could simply consume what it produces. It would mean a bottomless abundance of those items which a comfortable, dignified life cannot be had without! Of course, there is the problem of maintenance.

Long have I struggled to figure out that final problem. Some mechanism is needed to keep this magnificent, mechanical cornucopia chugging along smoothly. I soon realized this mechanism would need to be quite close to as sophisticated as a man in order to do the job in question! What vexation.

Sharp as my mind may be, that’s a task beyond the scope of my abilities. I might show you the fat stacks of drawings I drew of various rickety metal automatons on wheels and legs. The contraption which I meant to be the basic ‘handyman units’ which keep the larger machine in good repair, as well as maintaining one another.

Then it struck me. The orphans! What machine reliably performs every task that the human animal is capable of, except the genuine article? My little grease monkeys, brought in out of the cold, the relatively simple work of replacing worn out components fairly divided among them.

Is it wrong? I cannot see how. I meant to put them to work anyway. Only rather than pay them in shillings and pounds, they can now be rewarded for their labor with exactly what it is they need to live, and to go on working. Rare and lucky is the fellow whose own exertion so directly benefits him!

Picture it...like so many little bees in a hive, buzzing about, patching holes, ensuring its continuation out of simple self interest. What better motivator than that? Conventional wages pale in comparison.

The children will maintain the machine, and in return it will meet all of their needs, quite independently from society. A self contained microcosm of human civilization that’s sufficient unto itself!

Certainly you see the potential? This is not just another feeble humanitarian gesture, but a permanent solution to poverty! To hunger, to homelessness! One which will not die with me, but instead persist forever, by the hard work of those who depend upon it for survival.”

The rest were unremarkable pleasantries concerning the day to day operations of the Ministry of Child Welfare, the sort of compulsory but banal small talk which I can tolerate only so much of. I was about to open the second envelope when I heard a bell chime. Remembering Agnes’ insistence on punctuality, I tucked it back betwixt the pages, then followed a series of signs to the dining hall.