1

There’s nothing left for me here…yet I keep coming back. The official investigation came to a close six years ago, it’s not terribly likely I’ll find some vital clue that the cops overlooked. But wherever Natasha is now, I want her to know I didn’t give up so easily.

My family came to Russia nearly twenty years ago. Dad got a job with Soyuzmultfilm, a big animation firm headquartered just outside of Moscow. I was just a boy then, excitedly awaiting the birth of my little sister.

The film Dad was hired to work on never saw the light of day, a remake of the classic “Hedgehog in the Fog”. Not such a problem under Soviet rule, pay continued regardless of performance. He liked the creative freedom it made possible, but when the Soviet Union collapsed, Soyuzmultfilm more or less collapsed with it.

The studio survived as a leased enterprise, but ninety percent of the staff were laid off. My father was among the few who weren’t. The meager pay was just enough, along with what my mother made as a nurse, to keep us all in food and clothing.

I remember one winter, Natasha begged for a Dendy. She was too young then to understand the concept of money, and the rhetoric she heard at school and on television about “equality” and “a classless society” only further confused her.

Gorbachev had resigned a year earlier, but the curriculum at school did not yet reflect it. Nor the lingering Soviet themes in the media. A sort of widespread cultural disbelief, as we all witnessed the dream of global Socialism perishing before our eyes.

“Why is it Mikhail’s family has a Dendy, but we can’t afford one? What makes them different? What about Grandfather Frost, can’t he bring me a Dendy?” Each question like a knife in his side. I was forbidden to explain the facts of life to her, Mom insisted she didn’t need to know such grave things yet. That conditions might improve before she grew much older.

They didn’t. The next few years were the hardest of our lives. Law and order rapidly decayed. Gangsters operated openly in what were once nice neighborhoods, selling all manner of imported American products. Filling in the gap, I suppose, until domestic industry could be revived.

During those years, we often ate only every other day. The heat was turned on for just an hour each night before bed, so we could fall asleep. Natasha sought refuge in her beloved cartoons. In the mornings on weekends and after school every day, she never missed a chance to watch Peter the Possum.

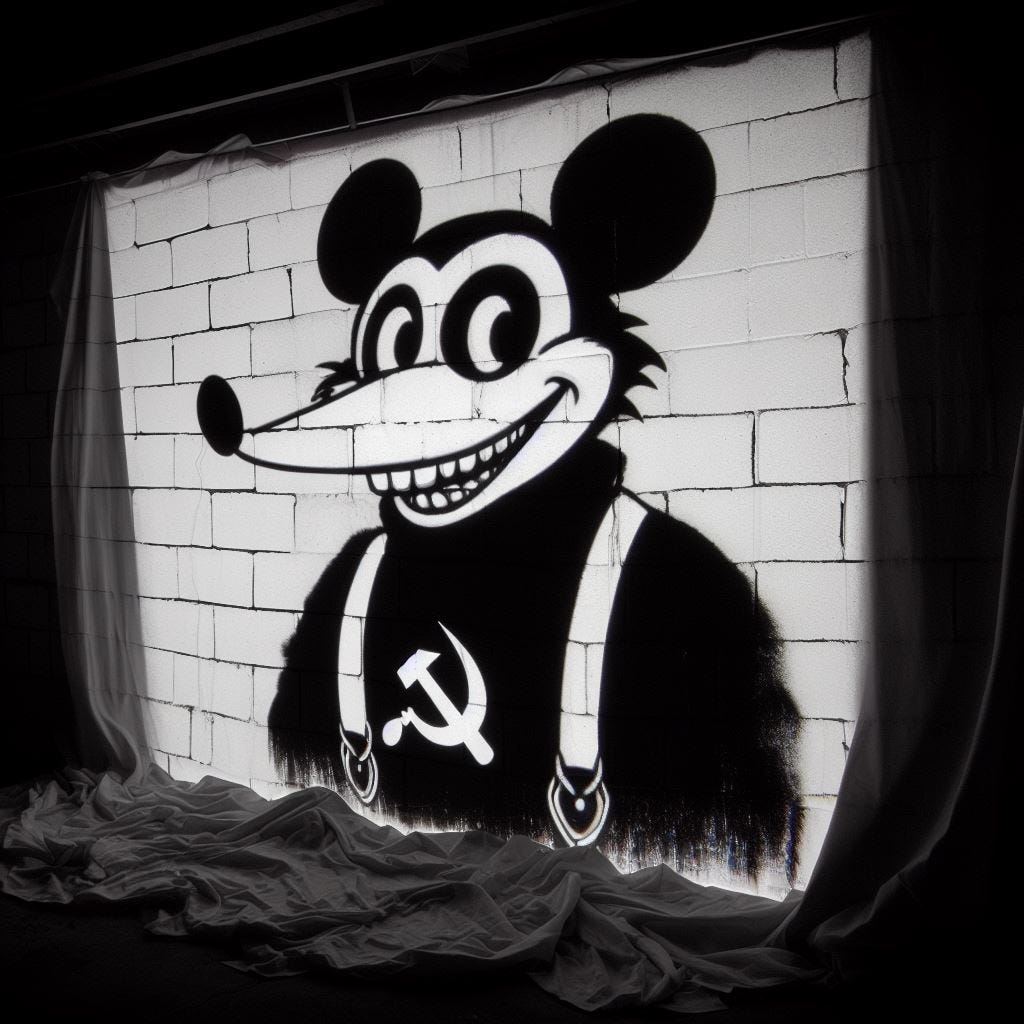

Before the collapse, Peter was a government attempt to copy the style of early Disney animation, with a view to using cartoons as a propaganda vector. Accordingly, about half the Peter the Possum cartoons I’ve seen have plots which in some way communicate the merits of Socialism and the evils of Capitalism.

Even when they first aired, they looked archaic. Peter wears the same big buttoned pants and suspenders as Mickey, and does that strange, constant dance all the cartoon characters at the time seemed to perform even while standing still.

Knees and elbows bent, then straight. Then bent, then straight. Squat, stand, squat, stand. A perpetual jig which background elements like hills, buildings and cars also danced in time to. “Dumpity doo!” he would often exclaim, usually at the end of sentences and for no obvious reason.

I recall an episode in which a gang of rats conspires to chop down the tree Peter sleeps in, then fashion it into a shelter so they can charge him rent. The transition between these plots and the post-collapse ones is like night and day. Peter suddenly seems much less concerned with politics and primarily focused on teaching children English.

Not much of it, mind. Simple phrases like yes, no, hey, wow, and so on. As we shared a room I was helpless but to endure Natasha’s repetition of basic English phrases while trying to focus on my homework...taking for granted that she’d always be part of my life.

When she got that free ticket in the mail, I initially thought nothing of it. Dad studied it more closely, as it bore the Soyuzmultfilm logo across the back. Only because he thought it such an interesting curiosity did I bother asking him about it.

“It’s an invitation to Cosmotopia, a theme park that was under construction by the state during better times. I remember colleagues excitedly describing the attractions back before the lease and wave of layoffs in ‘89. Last I heard the state abandoned the project out in the boonies.”

I asked why bother sending out tickets for a closed theme park. “Delayed mail, maybe. Still digging through store rooms full of packages from just before the collapse. I hear stories of babushkas receiving ten years late some letters from deceased sons who fought the Nazis, that sort of thing. They must have sent these free tickets out as a promotion in advance of the grand opening.”

It didn’t sit right with me, though I couldn’t put my finger on the reason until years later. Why invite Natasha? She was in diapers then. So much I should’ve realized, so much I should’ve done. Of course when Natasha found out, she demanded to go.

No amount of patient explanation that the theme park was now defunct would satisfy her. She was never a reasonable child, prone to tantrums and difficulties separating fantasy from reality. I would blame the cartoons, except Mom says she was the same way as a girl.

We just never anticipated she’d run off like that. Despite the stacks of drawings she’s accumulated, all of Peter the Possum. Despite warnings from her teachers that she only seemed to be growing less attached to reality with each passing year.

Each of us blamed ourselves when she vanished. Dad still thinks it’s because he was always working and basically let the television raise her. Mom for the same reason, and myself because at the time I was going through a phase where I wanted nothing to do with my family and spent as much time as I could with the boys. Looking for trouble, or making our own.

The police determined she reached the ruins of Cosmotopia by a commuter train which still travels out there, as some of the support buildings were rented out to other businesses after construction ground to a halt. Otherwise the stop would’ve long since closed down.

The employees of the storage business closest to the park insist they never saw her, but that the park is a popular haven for squatters, addicts and runaways. More than once I’ve stayed past sundown and glimpsed flickering light within the windows of the fiberglass Fairyland castle. The indoor campfires of vagrants and Krokodil junkies.

I carry a small knife with me but harbor no delusions about how safe I am in such a place. So apart from those few times, I’ve always made sure to leave before night falls. Even that is no guarantee. The train is often a moving flophouse for passed out drunks and dodgy looking gopniks in track suits.

Today the sky is the usual shade of grey. Wholly uniform, no blotches or gradation, just a matte grey expanse. As if it’s not the clouds, but the color of the sky itself. The sort of sky which makes you wonder if you’re really still on Earth.

Of course there are sparse trees nearby, and ragged tufts of struggling grass to remind you. But their colors, muted by the dim sunlight, sort of blend together. Like the trees, the grass, the mud and the train are all made out of the same “stuff”. I briefly wonder if I am too, or if I’m separate.

A light wind tosses dried leaves about the sterile concrete train platform as I step off. The station itself is a crumbling, derelict mess. Most of the overhead lighting has gone out. The remaining tubes flicker at random intervals. The concrete is cracked and worn, the signs are all rusted to shit, and there’s a thin layer of debris and garbage coating the surrounding area.

Cigarette butts, discarded candy wrappers, torn newspaper and so forth. The accumulated filth of human activity. Nobody comes to clean it up because nobody is paid to. Most likely nobody complains, either.

There’s a monument to Yuri Gagarin built into the entry gates. His face made from colored stones, many of them pried out of the concrete by vandals over the years. The inset sign is an advertisement for the section of the park that’s space themed.

They don’t bother to chain the front gates anymore, it never kept anyone out. I brought my bolt cutters anyway, as now and again I find some locked door, overlooked until then. The handles terminate in bent wedges such that it doubles as a crowbar, making it supremely useful for these kinds of excursions. Naturally, it also makes a serviceable club.

The other thing I’m never caught without is an LED head lamp. Before, I used the light on my phone in dark service tunnels until a disoriented junkie startled me into dropping it. The light’s now busted and the screen’s got a mess of cracks in one corner. Live and learn.

Once past the gate, I head for the fun center. “Fun” being subjective of course, having rather a different meaning in this country now that it’s under new management. The narrow selection of arcade machines languishing along the far wall of the stout little structure give no indication that they were ever sincerely meant to be enjoyed.

“Sea Battle”. “Magistral”. “Winter Hunt”. “Autorally-M”. “Radish”. “Safari”. All of them just barely sufficient imitations of some Western game. Usually Atari or Williams games provided the general design concept. Then the programmers, working for peanuts with government guns at their necks, phoned it all in.

The result is something comically rudimentary even for the time, and just barely playable. A waste of time and kopeks, though I suppose that was the idea. Their reason to exist was only ever to prove a point; that we Russians had every luxury under Communism that any American had under Capitalism, wanting for nothing.

The two soda machines in the room were similarly austere. One simply a grey steel box which dispensed carbonated water, and the other a Cil-Cola machine which was broken into and looted years ago. The first time I found it, out of morbid curiosity I cracked open the last remaining can and took a sip. I judiciously elected not to drink from the machines which dispensed into reusable, communal shot glasses.

Flat of course. Otherwise surprisingly inoffensive given the age. Tasted vaguely like Kvass. I used to power up the arcade machines now and again just for laughs, but there’s little point as you can’t save your high scores. That would constitute blatant competition, you see.

On my way from the fun center towards Fairyland castle, I paused to take a picture of the clown train. I often wonder who designed this and why they thought it would appeal to children, rather than traumatize them.

It’s a small electric train resembling a centipede, each section of the body its own wheeled car with a pair of cushioned seats, now thoroughly beaten up by years of exposure. The front is, for some reason, the rusted head of a clown. I’ve often seen kiddie rides of the same make and model show up on urban exploration forums, they make an irresistible photo op.

The park is divided into Cosmoland, Fairyland, Futureland, and Cartoonland. As the names suggest, the first is space themed, all of the rides named after and meant to represent historically important orbital missions.

Futureland is even heavier on the propaganda, as it is specifically the “global socialist future” being represented. The “housing of tomorrow” near the entrance always catches my eye. Disc shaped fiberglass pods, four to a cluster, stacked two clusters tall for a total of eight small apartments in each tower.

Each tower’s a different color, all of them now faded to pastels...in the spots where the paint hasn’t flaked off yet. Increasingly communal living in the future was simply assumed for obvious, ideologically driven reasons. That said, while they don’t look like much now, I’d take one of these pods over Krushchevka any day.

As I continued towards Fairyland castle, something new caught my eye. Same old building I’ve passed a dozen times before, but somebody must’ve been through here since the last time, as a mess of vines were cut away to reveal lettering just over a row of second story windows.

“Animation Center”. Presumably someplace children could learn how cartoons are made. Parts of the old facade still survived, yet more fiberglass. At one time making the building resemble something from a cartoon.

The majority of it must’ve been torn down since then, revealing the ugly, rectilinear concrete truth hiding behind it. It reminds me of a story I once heard in which a visiting American diplomat was taken to the Kremlin aboard a train which passed by fields filled with false wooden tanks and airplanes.

The intent, presumably, was to fool the diplomat into returning to the US with a grossly inflated impression of Soviet military might. That the train “just happened” to pass all of that hardware was something I suppose they hoped would not seem suspicious.

So much of how this country was run back then relied on carefully cultivated illusions. To fool the outside world, but also its own citizens. Not so different from this park. To the eyes of a child, Fairyland, Cartoonland and the rest would have an airtight appearance of reality to them.

Small but fully functional civilizations, populated by spacemen or costumed elves who, so far as the child knows, actually live there. All of it an elaborate farce, no deeper than the thickness of the facades masking the buildings. All to preserve the happiness of children who are none the wiser.

Natasha must’ve come here sincerely believing that she’d meet Peter the Possum. That his fantasy world she saw on television was a real place she could run away to. How it pains me now, that I was ever the sort of person she’d want to escape from.

What I wouldn’t give now to hear her repeating after Peter, word for word, sprawled out before the little black and white television set in our room. How vivid it still seems. Like something still happening now, a place I might physically return to if I focus hard enough.

That feeling is also an illusion. Perhaps the cruelest of all. That the past still exists, that the immediacy of these visions connotes reality. As if we should be able to travel as freely through time as we do through space. What it must be like for a bird with broken wings.

So often I find myself lost in thought. Reliving memories of Natasha so completely that it startles me to resurface from them. But during those precious periods of somber reflection, the vast gulf in time between where I am and where I want to be shrinks to almost nothing. It’s as if I’m right there with her.

So near, yet so far. No matter how convincing, I cannot reach out and caress her face. I cannot braid her hair. I can visit, but never stay. Observe, but never change anything. The natural order of things, surely? But then, why does this restriction feel so wrong? So artificial.

That was me, wasn’t it? And here I am. I was there once. Why, then, can I not return? The only direction I cannot move in is the one I most desperately wish to. Seconds ticking mercilessly by, each one carrying me further away from her.

There’s nothing like losing a loved one to make you contemplate the nature of time. It becomes a nemesis. A tormentor. The only barrier preventing your escape from Hell, back to the paradise you were swept from by the relentless passage of minutes, hours, days and years.

What do any of those words really mean? Does the universe know what a minute is? If there’s a smallest indivisible unit of matter, and a smallest measurable distance, could there also be an objectively smallest unit of time?

If so, time does not pass fluidly, but as a sequence of still frames. One after the next, after the next, quickly enough to create the illusion of movement. And if it’s true that events could have unfolded no other way than they have, the predictable chain reaction of so many atoms interacting with one another, then all of this was predetermined.

Something like a movie. So many still images strung together like film, all of us simply actors playing the only parts we’re able to. No small number of people find that perspective unsettling. Personally, I find it comforting. It would mean that there was nothing I could’ve done differently. That it wasn’t my fault.

The alternative is that time doesn’t exist. That what looks to us like the passage of time is just the accumulation of changes, more and more atoms out of place compared to how we remember it. If so, then time is truly irreversible. You’d have to manually move every atom in the universe back to where it used to be.

The past is destroyed by the future. Impossible to visit, impractical to recreate. Our memories, then, are ghosts. Lingering echoes of a world which no longer exists. I don’t know which view is stranger. That time isn’t real, or that we all amount to moving pictures with the appearance of life.

Upon prying the door open, I discovered one of the windows was busted. I cursed myself for not noticing sooner, else I might’ve just crawled in through it. A frigid gust stung my skin as I edged around the mess of broken glass on the floor, countless little shards sparkling in what little sunlight came in through the opening.

A light rain began to fall outside. Just as well. A whole new building to explore, exactly what I came looking for. And all things considered, not such a bad place to wait out the weather. A reception desk in the corner sat strewn with reminders of the past. Rolls of unsold tickets. A hand stamp, a coffee mug. Not even moldy inside, just a solid lump of dried black crud.

The lid of an electrical box mounted to the wall behind the desk hung open, revealing row after row of bulky, archaic fuses. It subtly hummed. Evidently this building also still receives power. As I proceeded further in, I found the floor littered with what I first mistook for overhead projector transparencies.

When I picked one up to study it more closely, I found it was instead an animation cel...depicting a very familiar monochromatic possum. More and more of them as I continued, until I couldn’t avoid walking on them.

Along either wall hung light tables of the sort used to display X-rays in a doctor’s office. Many with animation cels pinned to them, though the bulbs were long since burnt out. I swept my light across the far end of the room and, to my surprise, there was some sort of indoor ride.

Nothing fast or exciting like a rollercoaster. Rather, individual moving booths like the ones in haunted house attractions, or the educational rides that carry you slowly through a variety of life sized historical dioramas.

I searched for some way to reactivate them, but the only obvious control panel was rusted out. Wouldn’t have done me much good anyway. After edging past the halted people carriers for a ways, the track abruptly ended. Dismantled by someone, only a sheet metal floor beyond that point.

The ceiling, curiously, was also sheet metal. Both scratched up as if somebody’d been over them with steel wool. Bit by bit I worked my way down the darkened, serpentine tunnel. Soon I reached a section with working lights.

One of the walls in this section of the tunnel was lined with pull down projector screens. Tied to a motion sensor I guessed, as once I drew near enough, projectors mounted in alcoves along the opposite wall sputtered to life.

I doubled back, worried the sensor might’ve set off an alarm somewhere. Or that at the very least, the commotion might attract unwanted attention. That’s when I saw it. Laying on the seat of the nearest moving cart, perched on the end of the dismantled track.

Now, it could’ve been anyone’s stuffed Peter the Possum...if not for the initials drawn on the tag in black permanent marker. It knocked the wind out of me. All these years without finding the slightest trace, now I held Natasha’s own stuffed animal in my hands!

The police. The damnably corrupt, lazy police. They might’ve found this six years ago if they just searched more thoroughly. But they only ever do as much as procedure requires, if that. Anything more depends on how generously you bribe them.

I should never have taken their word for it. Should’ve gone searching myself the very day she disappeared, rather than wait for government stooges to half-heartedly bumble through this park before declaring it hopeless.

“NATASHA!!” I cried out. “NATASHA!!” My voice echoed down the remaining length of tunnel, meeting with no reply...until a scratchy voice answered back. Not from the end of the tunnel, but from just beside me.

“Use your indoor voice, little comrades! Respect the other visitors! Haha, dumpity doo!” I spun around looking for the source. The projectors, having warmed up during my panic, now cast moving images of a familiar figure on the pull down screens opposite me.

Black and white. Surrounded with momentary black flecks, dust caught in the film or defects from wear and tear. A certain possum in suspenders performing that familiar, perpetual dance. His beady little black eyes, unseeing, simply dark spots on film, nevertheless seemed to follow me as I headed further down the corridor.